four words for the art you love

Reviving Robert Hughes's generative quartet: lucidity, deliberation, probity & calm.

Earnest art students like me in the early 90s—showing up to class a little winded, furrow at the brow, paint stains on the ratty t-shirt—very often, we read Robert Hughes’s Shock of the New as a core textbook in modern art history. It has Hughes’s signature electric style: full of decisive opinion and vivid phrasing. Here he is explaining how you might think about post-war abstract Western painting:

In the Somme valley, the back of language broke. It could no longer carry its former meanings. World War I changed the life of words and images in art, radically and forever. It brought our culture into the age of mass-produced, industrialized death. This, at first, was indescribable.

Cultivating curiosity about the indescribable is one way to take an interest in paintings like Charmion von Wiegand’s Untitled from 1942, above. This painting is not only without representational images, but also left without title directives—because, in form and content, it surpasses or defies all words? So much of life does, after all—surpass and defy.

But ultimately Hughes was ready with words, with the interpretive description to help us get closer to making sense of art with language. He found ways to invoke the shifting sensations of modern life and to connect those changes to the visual culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries—a modernity that is still so much our own. On life, for example, mediated by machinery like train travel:

[T]he machine meant the conquest of horizontal space. It also meant a sense of that space which few people had experienced before – the succession and superimposition of views, the unfolding of landscape in flickering surfaces as one was carried swiftly past it, and an exaggerated feeling of relative motion (the poplars nearby seeming to move faster than the church spire across the field) due to parallax. The view from the train was not the view from the horse. It compressed more motifs into the same time. Conversely, it left less time in which to dwell on any one thing.

As a young person, I gobbled up Shock of the New and picked up Hughes’s essay collection, Nothing if Not Critical, for more. Hughes wrote a regular column on art at Time magazine for three decades, and to read those pieces, you’d find that he didn’t actually have a happy appetite for the new-and-shocking as such. If anything, he often reads like a class-A crank: impatient with any whiff of identity politics (in its “political correctness”-era form), ready to topple any hint of pretension in his withering prose, likening the phenomenon of the speculators’ art market to rapacious, cynical “strip mining.” I suspect that few art history courses place his words in the classroom now. He showed little interest in women or non-white artists of any decade. Skimming back through the essays, I found more than one baldly anti-Semitic claim. There’s a fighting-words defensiveness that is both useful to think with and sometimes blinkered in its narrowness.

Still—a string of Hughes’s strongest words I read nearly thirty years ago returns regularly to my mind. They’re from his review of a Chardin show in 1979:

To see Chardin’s work en masse in the midst of a period stuffed with every kind of jerky innovation, narcissistic blurting, and trashy ‘relevance’ is to be reminded that lucidity, deliberation, probity, and calm are still the virtues of the art of painting.

Consider how precise and generative at once this quartet is. I’ll offer just a few of the ways to think about Hughes’s list.

Lucidity is more than draftsmanship, and more than clarity. A strong illustration in a magazine ad will deliver what is clear, but a work of art must illuminate, must sparkle with its delivery, whatever that delivery may be. Lucidity may be ornate and refined or rough-hewn and muscular; it’s an inner quality, not merely a style.

Deliberation is challenging to achieve in any art form: the presence of multiple ideas or techniques being contested and considered, juxtaposed right in front of your eyes, but without the mess of pure indecision. When lucidity can join deliberation, achieving both an arrested dynamism and a clean luminous confidence, these two are at their mutually reinforcing best.

The latter two are harder to pin down without being reductive, but just as useful: Probity in its ordinary sense means “upright, with honesty and strong principles.” We’d never want to say that all art must pass a morality test in some simplistic “message.” Probity instead is the presence of a real proposal on offer—a strong engagement, the absence of the cynical gesture or the easy gimmick. Probity has the thickness of dimensional life about it, not sloganeering.

And calm. You have to resist the literal notion of calm—as in tranquil, or easy on the eyes—and think instead of something more like compositional resolution. Artists and critics often speak of a visual artifact as relatively “resolved” or as-yet “unresolved.” They mean this in its formal totality: Does the work deliver itself to the viewer with a kind of finished-ness about it—a repleteness, no matter how chaotic the subject matter or style may be? Even Guernica, see, has the first three plus calm about it. The frozen stillness of violence and grief:

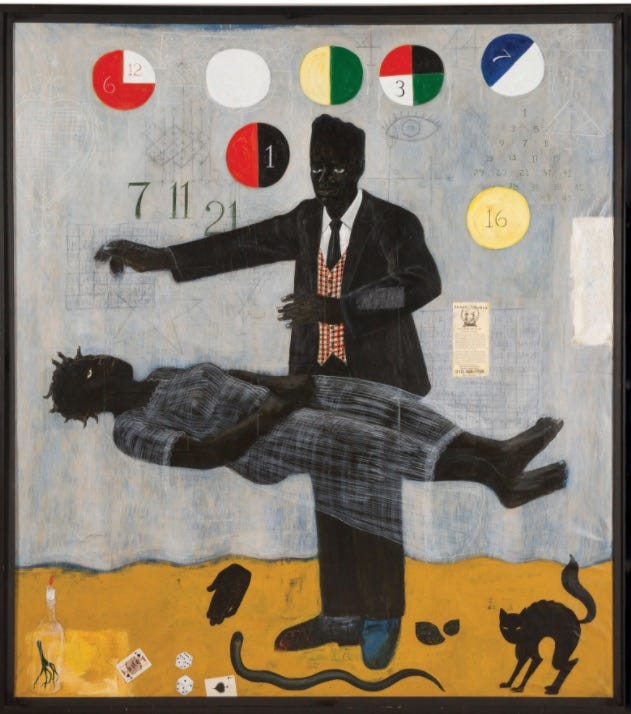

So does Kerry James Marshall’s When Frustration Threatens Desire. Probity in possibility, magic and history, a deliberation between the fanciful and the sinister:

But the really interesting thing about these four words is that—whatever Hughes would say—they productively map onto works outside of painting and sculpture, indeed outside of studio arts altogether. You can bring them to bear on much less popular, more challenging works of conceptual and social practice art. They help you avoid the flattening of nostalgic “standards” for art practice, if you’re inclined to reach for verisimilitude and craft-based skills in evaluating art. But they also help you circumvent the equally flattening effects of collapsing all art to politics. They allow for figurations of the social and political while insisting on expressive multiplicity and poetics.

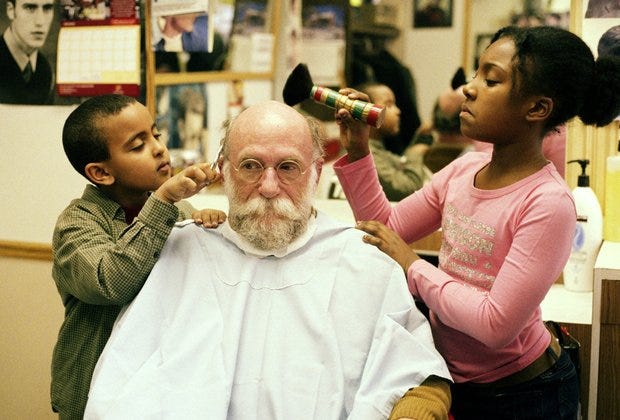

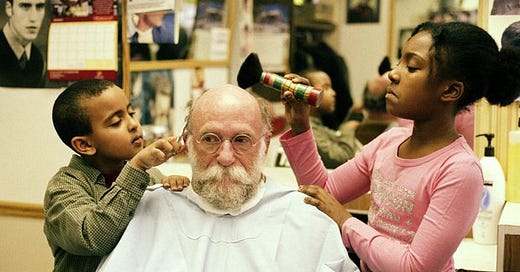

In Part 2, then, I’ll walk through ways to think about works of post-studio art with these same words in mind. We’ll look at Darren O’Donnell’s Haircuts by Children, pictured at the top of this post, at Felix Gonzalez Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers), at Fritz Haeg’s Edible Estates, at Laurie Jo Reynolds’s decade-long collaborative work called Tamms Year Ten, and more.

Thanks for reading. Some media highlights of my last month:

I loved this conversation with Rita Kozangon, Rachel Wahl, and Joseph Davis on liberalism, childhood, and Agnes Callard’s essay on “acceptance parenting.”

Benjamin Lipscomb’s The Women Are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics was just the right book at just the right time. I’m hungry now for the entire virtue ethics tradition, so send me some recs!

I thought Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Lost Daughter was perfection. Not because “bad mommy” stories are rare. There’s plenty of ambivalence-lit out there. But the quality of this film—its patience, its insistence on a genuinely rounded set of characters in the smallest moments, its absolute even-handedness about women’s ambition and mother’s love, achieved that simple-profound thing: it was, as they say, beautifully observed.

Know Your Enemy’s episode on the early career of Joan Didion at National Review and beyond was so good. Sam Adler-Bell, Matt Sitman, and Sam Tanenhaus as a threesome made that conversation so attentive and so lively.

Folks interested in disability arts, design, and politics should head over to Kevin Gotkin’s Crip News—a great resource for CFPs and other opportunities!

This was great. That excerpt about the train!!

I loved Hughes and your remarks on him, Sara, are wonderful and a tonic for at me today. Thank you.