[This is undefended / undefeated, a newsletter by Sara Hendren on big ideas at the heart of material culture: art, design, and engineering. You signed up for it at some point; unsubscribe at any time by scrolling down to the bottom. Or stick around and do please share this, as you like.]

In Part I of this post, we looked at four strong words for the art of painting by the critic Robert Hughes—lucidity, deliberation, probity, and calm. Those words are useful for artifacts of studio practice, things like drawings and paintings and sculpture. But what about when the work is conceptual, or temporal, or broadly a mode of performance that’s hard to capture in its formal qualities? I want to extend Hughes’s language for these works, especially what’s often called social practice art, a subgenre that many people find esoteric (“cool idea, but why is this art?”). Works like Haircuts by Children by the art collective Mammalian Diving Reflex.

This project is exactly what it sounds like: a short-term kid-run hair salon, enacted for a few days in cities for art festivals and other cultural productions, but where the haircuts are real, and the kids are really doing the cutting. Which is to say: children wielding sharps near the heads and faces of elders. As an art project! There is deliberation and probity in spades here, no?

Think about this simplest of reversals: young people charged with tasks that combine intimacy and responsibility, a work of caregiving that’s also tied up with vanity and self-presentation. Children at the helm for a brief second, and the question in the air that attends their leadership: Can they—can they do this?

And then the tumble of questions that comes after: If they can, mostly, do this task, would we recognize it if there are other tasks children could do, if our cultural norms would allow it? Do we attend enough to the inner lives of children? To their resourcefulness, their delight in being seen and known—and, perhaps above all, their being trusted? All of this deliberation in the lightest arrangement of elements, and with a big-hearted humor intact. It’s replete with that kind of calm that speaks of resolve. You see this project, even in a few images, and you think: How simple. How strange. Why not? And what if.

Mammalian Diving Reflex says they go “looking for contradictions” to set up in a theatrical, sometimes useful, always absurd way, and that they proceed from principles of “generosity” and “abundance,” which are the strongest forms of probity, after all. Social practices often do this—putting on performances but not in their formal, stage-mounted, ticket-selling sense. Instead, these works often “trigger a temporary condition” like this one, in the bet that most people of all ages will bring their best selves when entrusted with the highly unexpected. MDR call it “social acupuncture,” and they’re not alone: Social practice artworks often provide a small shift in the system of ordinary relations, intended to estrange us from our default categories and charge our perception with new—renewed—questions. (See MDR artist Darren O’Donnell’s book called Haircuts by Children for more.)

Note, too, that there’s no sanctimony literature looming over this project—no winking at the audience about some partisan idea in its meaning. It resists that easy read; there’s no self-congratulation here. The art is not realized in skills-based, studio-produced contemplative objects, but neither is it a “happening” as a message-ridden screed. It’s something else. A social practice artwork like this has light and air and questions about it, deliberative and probing.

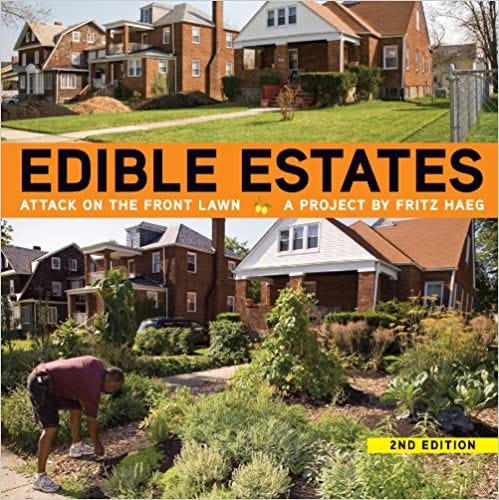

The same kind of spirit runs through Fritz Haeg’s Edible Estates:

With the sponsoring of museums and other art institutions, Haeg helps people turn their front lawns—usually dedicated to water-sucking ornamental grass—into fully functioning gardens. As the project’s book cover (below) says, it’s an attack on the arbitrary suburban standard, but more importantly, it’s a convivial proposal for a distributed agriculture in the places where it’s not currently expected. An attack in the form of a party, a punch with a grin:

Why, you ask, is this an art project? Why is it sponsored as such? Why call it a “project” at all?

In the same spirit of kids giving haircuts, this project is deployed as a what if question—it’s meant to suggest a possible future (again, that’s the strong principle of probity) while also defamiliarizing the status quo. This project could, yes, be an earnest initiative from your local gardening advocates, or a top-down project from your region’s city planners. But rolling out an idea like this as a bureaucratic thing—an initiative—automatically invites skepticism, pushback, and limited debate only among people who already care about the issue, whether for or against. As a social practice art project, this work has a wily joyousness about it: a form of culture that is both useful and expressive at once, and one that gets into the public eye as a prototype to think differently about the norms holding up the way things are. Lots of HOAs would get in a snit about some rogue gardener bucking convention. But an artist might galvanize a community with this lucid reframing of the world around you: an invitation to turn extant green space, now a site of useless, endless mowing, into raucous and beautiful front-lawn food.

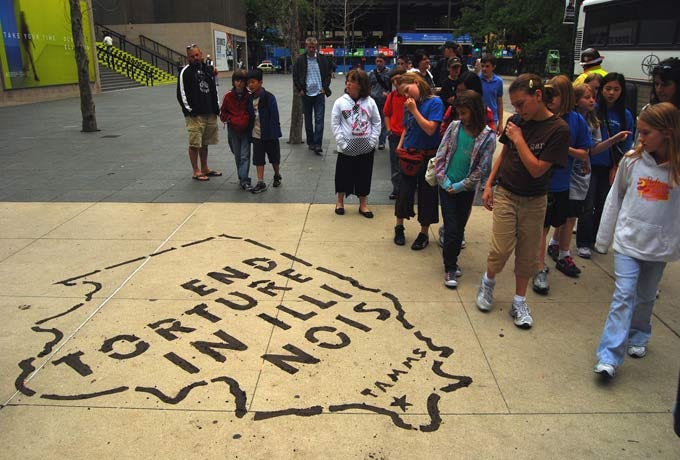

Sometimes, of course, social practice work is much more high-stakes and overtly political. One of my favorite art works of all time is Tamms Year Ten:

The artist Laurie Jo Reynolds was one of the chief organizers on this five-year project initiated to close Illinois’s “super max” Tamms prison—where an extreme, truly unimaginable style of solitary confinement was carried out for 15 years. Inmates were first brought to Tamms from other prisons as a radical, one-year measure of shock treatment for behavioral concerns. While there, they had almost no interpersonal contact at all: no group activities, no phone calls, meals pushed through the door, and exercise carried out alone. But what had been designed as a temporary measure often turned into long-term solitary. Tamms opened its doors in 1998. By 2008, about a quarter of the 500 men inside had been held there for the entire decade. Tamms Year Ten was a coalition of people who lobbied, cajoled, pressured, protested, collaborated, organized, photographed, wrote letters, and did a hundred other incremental, patient tasks to get Tamms closed down. And in 2013, they succeeded.

There was recognizable art involved, like this photograph above. Photo Requests from Solitary was one effort of the Tamms project, in which an incarcerated person could request a photo of anything, real or imaginary, simple or outlandish, and a volunteer would be matched to set up and take that photograph and send it to the requester. You can read about some of the requests here, like this “Big Cross” image:

BIG CROSS — Willie, 2011. Willie wanted his family and volunteers at Tamms Year Ten to pray for his deliverance from Tamms, so he asked for a photograph of a vigil at Bald Knob Cross, located in southern Illinois. The group traveled to the cross, held a litany of song and prayer and celebrated with a dinner. The next day, they drove family members to visit loved ones at the [Tamms section of minimum security] prison. After 36 years in different prisons, Willie was transferred from Tamms. He was paroled in July 2012.

A photo as a tiny (calm?) gesture of exchange, an acknowledgement of the wishes and needs of a single person, and a gift of imagination. A photography project at one-to-one scale, while simultaneously tackling the giant behemoth of the Illinois state correctional system.

Reynolds calls this—the whole project, with the lobbying, the long meetings, the strategizing, and the photography—she calls it “legislative art,” but not in a self-serious way. It’s the shapeshifting, deliberative nature of the organizing work that’s so shrewd here. It’s an artwork, not a fundraising nonprofit. It’s an artwork, and not easily capture-able by commercial interests or entrenched state politics. It’s an artwork, so it can come to an end. No need to invent reasons to perpetuate its life. It’s not only an artwork, of course, and maybe you could do the exact same thing outside the realm of art and get the same results. Maybe. Does it matter? As an artwork, Tamms Year Ten puts forth a white-hot lucid idea—an idea the late Paul Farmer might have called an “Area of Moral Clarity,” or AMC: that extreme solitary confinement is torture.

Reynolds says they had to believe in the capacity of elected officials to do the right thing—and that in many key cases those lawmakers did, in ways that surprised the organizers. Tamms Year Ten didn’t just one-off protest for the good media coverage, though they did do that. They did the visible things and the invisible things. They built healthy relationships. They stuck together, kept their eyes on the horizon. The moms of those men held in Tamms, former incarcerated advocates, other conscientious volunteers, and artists: lucidity, deliberation, probity, and calm.

[The link is to a speech and panel discussion in which Tamms Year Ten won the Annenberg Prize for Art and Social Change. Reynolds and three collaborators speak about the work at length.]

Thanks for reading, and for your notes and replies, as always. More newsletters to come about design, bioethics and technology, and teaching.

Some media highlights and news:

—I talked with Ryan McGranaghan on his Origins podcast about healthy relationality online, art in the context of engineering, faith, and more. That was an exceptionally good conversation and a joy.

—I mention Becca Rothfeld’s essay “Sanctimony Literature” above. Seriously, have you read it? Rothfeld is one of the most interesting critics working today. I’ll read anything she writes, along with the words of Lili Loofbourow and Meehan Crist.

—This spring I’ll be co-hosting three episodes of The Futures Archive, a podcast about designed objects from Design Observer. Lee Moreau and I will be talking alongside experts about defibrillators, insulin pumps, and refrigeration in healthcare, a group of topics loosely organized as “health and safety” in design.

—S. G. Belknap’s “Sex and Sensibility” in The Point was one of the most original things I’ve read this year.

—Greta Gerwig’s Little Women has cast its spell on my children, especially my thirteen-year-old daughter, in the same way it case its spell on her mother more than three decades ago. I just marvel, as we all do, that a century-old story can keep reaching so far outside its time. The line that I keep thinking about is the one Alcott gives to Mr. March in a letter from the front: a hope and belief in the work of virtue as a practice, that his daughters “will conquer themselves so beautifully.”