It’s a boring truism that the headlines are a distortion machine. I’m guessing that readers here find themselves mostly unrecognized by the mainstream news outlets stoked by social media click-chasing. I bet, like me, you’re a mix of left-or-right, fast-or-slow, protest-or-cooperation, institutions-or-grass roots axes when it comes to the big political issues, and in that mix lies the state of Campus Culture. I’m betting that we share a mix of concern and skepticism about diagnosing the contemporary education zeitgeist, and that some of you, like me, are wondering how to cut past the algorithmic noise and lightly shore up the project of teaching and learning. So—to that end—I’ve got a plan for Week One in both my new classes this fall, and I’m curious what you think about it.

[Hi there—this is undefended / undefeated, a newsletter that you signed up for at some point. Thanks for reading! Some of you reported that you enjoyed the audio version of my last installment. I enjoyed making it, and/but I found it unsatisfying to only publish the written version in a lightly edited transcript. I want written work to read as such—with precision and economy—and I want audio to shine in its best informal light. So I’ll do what I observe among other Substack writers: publish both versions back to back, so you can consume and share as you like. Unsubscribe at any point; link at the bottom.]

On any given weekday morning in a semester, with a group of very specific students-and-professor who agree to meet and knock around a bunch of ideas together, things are generally not unfolding as dramatically as the sensational news stories would have you believe. I say this from my posts at four different lefty east coast American institutions in the last decade. It’s not that adversarial. And yet—there is a conflation of language with harm that’s afoot, a new idea to grapple with together.* It’s similarly not the case that students are commandeering the classroom with approved or cancelled topics. And yet—there is a kind of easy and expected ritual in the way students see texts, if left unchallenged: texts as hamfisted negotiations of power and little else. It’s not the case that politically conservative views are verboten on campus, but, well—there is an unspoken progressive orthodoxy that’s unexplored at the foundations. It’s a delicate time, and, yes, I’m worried. But above all there is this: a hunger among young people for difficult ideas, for the big reasons why they’re important, and for the skills to hold complexity aloft, unresolved and sometimes unresolvable.

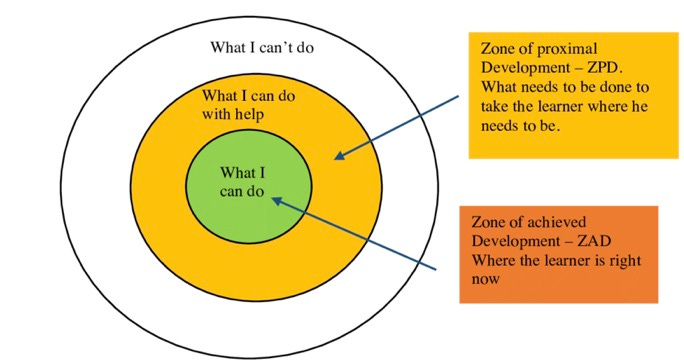

Some of you read my piece about the Zone of Proximal Development, right? Let’s look at this graphic again:

The biggest mistake that teachers make is trying to take students from what they can do to what they can’t do in leapfrog style: hopping from the one to the other with the trust that throwing folks in the deep end will always, by semester’s end, deliver. Sometimes that does work. But—trust me, I’ve learned this the hard way, repeatedly—without the slow-walk structures that bridge from can’t to can, you’ll be losing a lot of people along the way. The ZPD is that space where intentional teaching lies: modeling in behavior and practice, making the how into part of the formal curriculum, assessing process alongside outcome.

And—okay—let’s say this is all basically well and good for domain-based coursework. It’s less obvious how you create a culture of open-handed pluralism and healthy contestation in general: as an ethos, a commitment, even a vibe for running any classroom. How do you map the Zone for an amorphous polarized mood on campus? For the subtle creep of flattened political discussion, intellectual foreclosure, timidity in the face of hard questions?

When generations shift, when the zeitgeist changes, you can be frustrated that students no longer come with that same green zone of “can,” unaided. You can rant about how they’ve been raised. You can diagnose the cultural norms and where they come from. You can blame students, administrators, Higher Education At Large. You can retrench to your established classroom norms, unexplained. Or you can shift the Zone one orbit back and scaffold to the place where you’re headed. Name and explain what the gathering of the classroom is for, and then walk students through the paces, Socratic-style, to arrive at what it takes to embody that purpose. For me, that purpose is most elegantly expressed in Danielle Allen’s idea of education as participatory readiness, which is a form of civic agency.

I’ll be reading Allen’s piece with students between Week One and Two, and when we convene in Week Two, we’ll talk about “readiness” as a paradigm for our provisional community. What do you need to be ready for? And how would you know you’re ready—ready with a lot of resilience around the edges, ready for ideas and decisions you’ve rehearsed in class, but also ideas and questions that will be new to you in some ten, twenty, thirty years’ time? At my institution, like so many others, we often emphasize what Allen calls “professional readiness”—sometimes as an ROI for the expense of college, but sometimes from an earnest distributive logic for learning. More access to educational goods for the professions, Allen says, is celebrated for its democratizing effect in more fairly distributing cultural and economic capital.

Professional readiness is good, necessary, important! But “political choices determine the rules that shape distributive patterns,” writes Allen, so “it makes sense to focus first on political, not economic, equality. And if we choose political equality as our orienting ideal—empowering all to participate capably in the life of a polity—a different view of education’s purpose, content, and consequence comes into view.”

Allen goes on to name and define three practices of participatory readiness that prepare students for the civic agency that she sees at the heart of political equality: 1) disinterested deliberation, 2) fair fighting, and 3) prophetic reframing. Read the whole thing for succinct definitions of each of these modes, and the call for ordinary citizens to recognize and choose among them, shift between or recombine them. The classroom is an ideal setting for practicing each of these, in a mix of capacities that includes “social diagnosis, ethical reasoning, cause-and-effect analysis, and persuasive argumentation.”

So my students and I will talk about readiness, about disinterested deliberation, and about what that kind of skill requires: open-handed inquiry, curiosity, a commitment to disentangling people from their ideas, and so much more. But the scaffolding for the why needs to be, well, iterated, not just cursorily, cryptically re-iterated—because it’s not a generational assumption. Readiness needs championing, and I think students will get it when they think it through in the ZPD.

We’ll also read Wendy Brown’s recent interview in the NYT, with specific attention to the “containers” on college campuses—rooms and settings that make different kinds of engagements possible. This is a very simple but necessary idea: You do, yes, bring your whole self to college, and colleges are more and more set up to honor all those facets of self, in spaces and groups and supports that are far outside the academic alone. But following that very reasoning, the classroom is one container and not designed to be all things to all students at all times:

Campuses are complicated spaces, because they aren’t just one kind of space: There’s the classroom, the dorm, the public space that is the campus. Then there’s what we could call clubs, support centers — identity based or based on social categories or political interests. It’s a terrible mistake to confuse all of these and imagine that the classroom or the public space of the campus is the same as your home.

It’s a design metaphor here: the campus is a series of envelopes, as architects say, that specialize in certain kinds of readiness and not others. For disinterested deliberation to work in the classroom, we have to agree that it’s not primarily a therapeutic space. Or a political club. And so on. I’m betting students will come along for this venture.

*On language and harm, I recommend Sarah Schulman’s Conflict Is Not Abuse and Michael Roth’s Safe Enough Spaces.

Update: After talking with Howard Gardner and Wendy Fischman about the ideas in their book The Real World of College, I think I’ll add to my Week One list this short blog post by one of Gardner and Fischman’s research interns, an undergrad who course-corrected in her own college trajectory:

[L]earning about “mental models”—how participants view the purpose of college and structure the experience—spurred the most personal reflection. As part of the holistic analysis, I coded each participant according to four distinct approaches: inertial (e.g. “I go to college because that is the next step after high school”), transactional (e.g. “I go to college to get a job or go to graduate school”), exploratory (e.g. “I go to college to try new academic areas, different activities, and meet new people”), or transformational (e.g. “I go to college to grow and develop as a person and learner”). In considering these mental models, I couldn’t help but imagine how I might categorize my own friends and acquaintances. I had “transactional” peers who went to college with a predetermined vision of what courses they would take and what job they would land after graduation. Interestingly, these were people I often envied; they seemed to have had it “all figured out.” On the other hand, I had “exploratory” friends operating on five hours of sleep as they were involved with as many campus activities as they could squeeze in (in addition to their coursework), hoping to try out and try on as many diverse experiences as possible.

What about my own mental models? It has been a journey.

—Runner’s high in these hot days courtesy of Alpinisms, School of Seven Bells. Say it with me: I am under no disguise.

—I read and loved Phil Christman’s How to Be Normal this summer. Planning to use a piece from that in my new nonfiction class this fall! Phil’s newsletter, The Tourist, is also great. Recommended.

—I wrote a long piece for Wired magazine’s Ideas section, about how smart home tech is a new frontier for prosthetics:

[A]ssistance now shows up as a mix of independent housing, animal companionship, smart home technologies, and remote-support videoconferencing. It’s a constellation of high-tech and low-tech in distributed, networked tools, many of which are ready to hand, seamlessly integrated as ubiquitous features of everyday life, which can bridge some of the logistical barriers to employment.

And a constellation of technology is indeed the proper metaphor. There’s no one way to dominate this market—no single system that will outfit a living space or workplace with “universal” features for accessibility. There won’t be a single “curb-cut effect” for this digital world.

—I co-hosted three episodes of The Futures Archive podcast for Design Observer, all on objects in the big theme of “health and safety.” One is about the defibrillator, one on refrigeration, and one on insulin pumps.

If you’re into RSS, you can read a bunch of small excerpts and notes on my blog, but here’s a quick digest:

Roe vs. Wade requires the intellectual virtue of acknowledging a hard problem.

I’m organizing my nonfiction class readings into tour guides, persuaders, portraitists.

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò on deference politics vs. constructive politics.

I loved reading about Kurt Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem as a west coast skeptic.

Hi Sara, definitely have a lot of thoughts on this. I believe the classes you're teaching are Olin classes? Looking back on my experience on campus, I think it was difficult sometimes to have conversations because we had so little grounding in any sort of "humanities" literature, and as such words or ideas got thrown around without even a shared understanding of what things mean; e.g., if we're talking about "intersectionality," what are we actually talking about? Whose ideas are we invoking when we use that word?

Building off of the idea of readiness, one thing that I've found helpful in my post-Olin intellectual life is to view the act of reading a text as an encounter between you and a piece of writing, one which has an intellectual genealogy that you probably aren't yet aware of, and whose ideas have also been taken up by others towards various ends, some of which you may agree with and some of which you may not. The ZPD is actually sort of an interesting example of this. In my grad classes, Vygotsky was fairly contentious because he was known to apply his own theories toward ends that were pretty racist (or at least Eurocentric), and that generated a lot of discomfort with the idea of aligning oneself with his theories. At the same time, if you read up on Vygotsky, you find that he was also quite Marxist in his beliefs, and that the ZPD was part of his broader theory of the mind as inherently based in social and intersubjective meaning-making. Today, many of the scholars in my field doing crucial, justice-oriented work are broadly "Vygotskian." These facts can't be summed up into a single satisfying conclusion, but I've found it comforting to view each writing as part of a broader historical context and body of work, one that we can explore in search of a clearer sense of meaning.

Sorry for the long response; very interested to hear how the classes go. Hope you're doing well!