the design of time

Teaching and learning in the Zone of Proximal Development. And: what writers can learn from labor organizers.

[Image of NYC nightlife via this article over at CityLab: “So You Want to Be A ‘Night Mayor’”]

This summer I wrote an essay for the New York Times about using the clock—the hours and minutes of the day—as a design tool. It’s not a new idea; see an article about the phenomenon of the “night mayor” in cities around the world, for example. But it’s one that got renewed attention in the makeshift and quick-change artistry that had to happen under COVID: streets with designated uses that changed between day and night, shopping hours dedicated to older adults or people with compromised immunity, and, in my own neighborhood, an expansion of a time-based “park”: a long-loved street that closes to cars on Sundays in the warmer months of the year. For the last two years, we got double that amount of “park” space, Saturday and Sunday, just by erecting and dismantling barrier gates at several intersections, morning and evening, letting the streets blossom with walkers and wheelers of all kinds. It’s time that transforms the status quo into something else, without the commitment (and potential harm) of a permanent intervention.

In the piece, I mention one example of using time for making institutions more accessible: the Morning at the Museum program that runs at all of the Smithsonian’s 14 sites in Washington, DC. It’s not the only place where disability occasions a creative reinvention by means of the clock. I might have written about how movie theaters and playhouses all over the U.S. designate some of their performances as “sensory-friendly,” wherein volume and lights are dimmed from their ordinary settings. Or the “Green Man +” program in Singapore, in which an augmented metro card for seniors and people with disabilities will extend an ordinary crosswalk’s countdown time by a dozen or more seconds, after which it reverts to its standard allotment. And the whole idea for the essay arose from a conversation I had last winter with some directors at a community dance space. They were struggling with two kinds of access needs: a group of deaf dancers who wanted to use pulsing lights on the walls to track the rhythm of music, and other performers with epilepsy who couldn’t be around those lights when they were in use. We talked it over and arrived at the clock as their friend: Designate some nights for the lights, and some nights without. Sounds obvious, I suppose, in the abstract. But when people think design—and perhaps especially when they think of accessible design, it’s easy to get stuck on hardware, software, ramps and elevators and curb cuts. We look to what’s known and tangible, and we think less often about the the invisible tool of time to bend and flex the structures of the world.

Folks who know disability studies will know that this whole discussion begs for the naming of crip time. I have a whole chapter in my book called Clock about this very idea, and it’s a powerful one: how industrialized, economic time serves to shape our bodies to its exacting ends, and how disability—the needful, nonconforming body—militates against that rigidity.

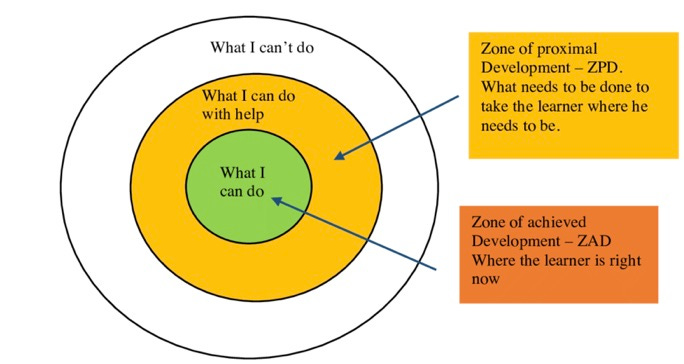

But I didn’t include crip time in the NYT piece because I’ve thought hard about Lev Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development:

[Image via]

You can go deep into Vygotsky’s psychological theories of education, or you can, like me, productively cherry-pick this idea for its useful reminder: The learner, whether student or reader, can come with you from their current zone, what they already know, to the next developmental place. But if you try to jump them further than that place—beyond the Zone of Proximal Development, too fast or too carelessly—you’re likely to lose them. Not because folks aren’t sophisticated or smart or even willing. It’s just a simple fact of cognitive load and scaffolding: To introduce a novel or surprising idea, you have to build the conceptual bridge from what’s provisionally shared to the new and unexpected.

I think about this all the time. Who are my readers, and what assumptions might already be in their minds, and what’s the next possible leap we could make together? I didn’t think the audience for an article about time and design in a pandemic could travel all the way with me to crip time. It’s there in the disability literature for folks who want to go deeper but couldn’t be seamlessly reached in my piece.

It’s not as if all reading is teaching in a unidirectional, condescending way, from writer to reader—far from it. Every writer is writing precisely to think through and try to understand some set of ideas better, for her own sake as well as the reader. But the Zone should still be in one’s mind, no matter your narrative medium. And too often writers get tied up in an inside-baseball version of their topic, because the tacit reader in their mind’s eye is their peers: the people they speak to in professional development contexts, or the other books in their field, or their various social circles. But the scaffolding for a wider audience requires a much more rigorous attention to the Zone of PD—if, that is, you want to reach the reader who’s not already with you. If your audience is that of peer experts, then your Zone will be adapted accordingly! But if, like me, you want to introduce your interests to folks outside that set of already-convinced readers, then a disciplined attention to the Zone, and the cuts to your prose it will likely require, might be useful.

I often think of this kind of writing in a framework the labor activist Jane McAlevey describes: knowing the difference between organizing and mobilizing. Mobilizing, McAlevey says, is the kind of catalyzing work that activists do when a group of people agree with one another about some problem at hand. Mobilizers serve to get those folks off the couch and into action, together, toward some cause they already believe in. But organizers, she says, are people who work to find common cause among people who don’t already agree. (Folks on the left, she says, regularly confuse and conflate these two things, much to their peril, and I agree.)

In McAlevey’s case, that might be organizing among hundreds of hospital staff, say, for better working conditions. To do that well, she says, you don’t start with action plans and resentment and in-group speak. You start with conversations that surface people’s core values and real wishes, and you build from there. Not everyone can do it, McAlevey says. Some folks are so sure they’re righteous and correct that they can’t be bothered with the patient work of building common cause. It’s the most humanizing, belief-led work there is: starting with foundational premises, and building, in the Zone of Proximal Development, to some shared idea of a desirable world.

Now, naturally: The world needs both mobilizing and organizing. In labor unions and in ideas-based persuasive writing. But getting clear about which is which—and which you’re suited and aiming for, and the possibilities and limitations of each—is some substantive fraction of the practice.

When I think about the most patient organizing in action, I think about Dorothy, who’s profiled in this short New Yorker documentary. She went one-on-one to the neighbors in her rural Alabama county to spread the word about vaccines in its early days. Most of the footage is Dorothy calling, visiting, inquiring, cajoling, reminding. Each conversation is building common cause. “I don’t give up on people,” she says.

Thanks for reading. Wishing you all a peaceful-enough end to 2021, and a truly brighter 2022. Much more to come here.

I’ll be Lecturer in Architecture at Harvard GSD this spring while still on sabbatical from Olin: one class on disability and design.

My talk on critique and repair at the MIT Media Lab is up on YouTube now. I loved speaking with Zach Lieberman about art and technology, the unsatisfying language of STEAM, and building a healthy and thriving lab culture.

And: my book received an Honors designation in the Massachusetts Book Awards, in the Nonfiction category, alongside Nicholas Basbanes’s Cross of Snow and the winner, How to Make A Slave and other Essays, by Jerald Walker. I’m told there will be a ceremony at the MA state house—you know, someday! It’s a thrill nonetheless.

The zone makes so much sense! Wish I'd had this idea when my kids were younger — better late than never! :)

Sara, I love Vygotsky and your use of him is incredibly creative and so different from the way so many psychologists see his work. Your article makes me think of an activist geographer I know.

Do you know Don Mitchell? He's an Emeritus Prof from Syracuse. He's done a lot of both academic and activist work in parks in Boston where food vendors are not allowed to give food away. As the punk band Gang of Four says, "This culture gives me migraines." My best, Randy