Prototyping, you may know, is the early try-and-see process that ushers some new idea into being. It takes whatever materials are ready at hand and makes a three-dimensional “sketch” of what’s being proposed—a way to think through your idea and test its merits before you commit to building the real thing. Prototyping generates the messy tabletop version, the wobbly fledgling creature: a tennis ball and a rubber glove, say, and dowels and staples, maybe some hastily patched duct tape. You have to squint to see what’s being offered, but it’s there. I learned to love prototyping at Olin College of Engineering, where I was a professor between 2014 and 2023. I’m not an engineer, and that may be why I could see prototyping with a beginner’s mind. I never fully grasped the details of engineering mechanics, so I never got caught up in the minutiae of the parts-and-systems. It was always the poetry that got me.

The poetry of prototyping is the vulnerable attempt, the tangible trying. The willingness to venture, knowing it might fail. The investment of commitment to even the most sloppy version of a possible newness. A thing being prototyped is trying to get born, unfolding right there in front of you. And all the conversations around that thing have the quality of willed belief: What if it was half as big? Twice as long? A different shape around its edges? Dozens of questions that are all really just versions of the best and only question in design, at the end of the day: Could it be otherwise?

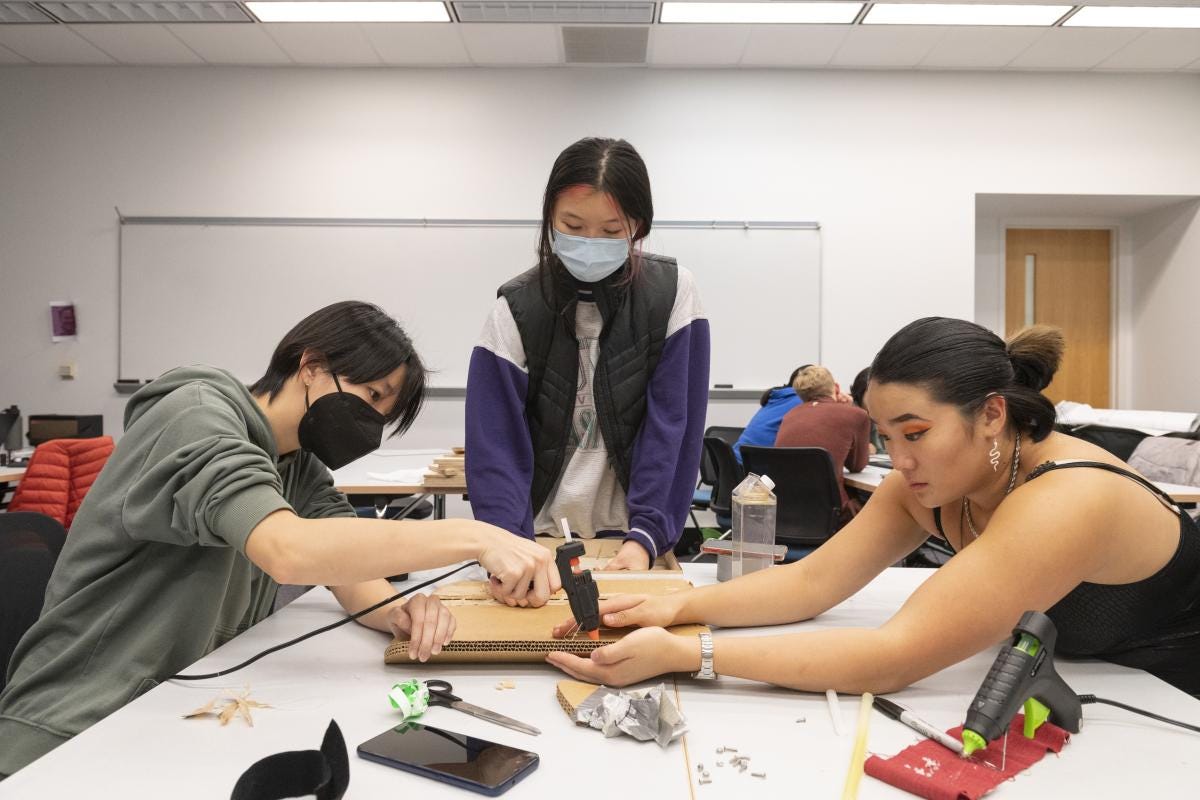

One class I team-taught at Olin was called Design Nature, a course all first-year students take that includes one solo and one group design assignment, both inspired by mechanical operations found in living biological systems. The group assignment is to make a play experience for fourth graders based on animal behavior — an interactive game based on, say, the way goat kids leap, or the way honey bees waggle. The students interview parents and teachers of fourth graders, do some developmental research, and then start prototyping. Like that image above — you build something so that you can think with that thing. So you can ask yourself candidly: Is the scale in my head really working in dimensional space? What are its functional qualities, and what are its dramatic qualities? Can you use that open mouth to catch balls? How easily, or how awkwardly, or how efficiently should it operate? What’s this experience supposed to work like, but also: what should it feel like? The prototype will teach you.

And then, near the end of the semester, local fourth graders come to campus and play the fully designed games. Hilarity ensues! Or maybe it doesn’t. Designing something charismatically playful is hard. I mean—have you tried?

It’s a quest to find the right combination of timing, surprise, and absurdity. No amount of mechanical prowess will guarantee you the sensibilities you need to design these qualitative features.

All the fourth graders get clipboards and forms to fill out about students’ games. Kids won’t flatter your ego. If it’s not fun, you’ll know.

Jennifer Banks helped me see that prototyping takes place inside a grander thing: natality, the ongoing creative force of newness that powers the world. In her book, Banks says most of us are lopsided in turning so much of our attention to the universality of death. We should and do reckon with mortality, mourning the many endings all around us. But we let death obscure the counterpart universality of birth, of natality. Birth “has long hovered in death’s shadow, quietly performing its under-recognized labor,” she writes. She means human birth itself, yes, but also the small-b births that form a pattern of everyday newnesses, the dying and rising that shapes our nights and days and seasons.

Kafka announced to us long ago that the meaning of life is that it stops. True enough. But Banks walks the reader alongside seven intellectuals who took seriously the bookend of starting: new life, fecundity and generativity — and, in my mind, our many distributed practices of creative midwifery that get new ideas off the ground. Hannah Arendt is one of Banks’s chief companions on natality. She thought our creative beginnings are not just universal but necessary, a strong stance against authoritarianism, a rebuke to brute force power. Natality, for Arendt, embodies the amor mundi, an outwardness and expectation of beginnings, of making room for others. She called it “the miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal ‘natural’ ruin.” And the amor mundi has to start somewhere. Not just the endless talking about what the world should be like. Prototyping is beautifully restless and insistent: Show me how. Let’s start.

Do I make too much of a small thing? Maybe. In my own native practices of artmaking and writing, there are plenty of easy words for things like prototypes: drafts and sketches and studies. But those practices were so long in my habits that I’d stopped seeing them. I was out of place in the lab, bewildered at the white boards covered in equations, the arcane physics jokes, the tangled rainbow of wires extending from a circuit board. The messiness was joyful and familiar, but the tools and detritus were new. Engineering was both muse and stranger. But prototyping I recognized.

In my faith tradition, birth is joined to death across the liturgical year, and it’s seldom without emotion that I can speak aloud the ancient text from Isaiah when its recitation comes around. Prophetic verse offered in the present tense:

See, I am doing a new thing! Now it springs up; do you not perceive it?

A newness arriving now, and now, and now — natality as a fundamentally generous and emergent architecture of the world. We look the many faces of death square in the eye. But birth, too, is death’s (and our) companion.

Last fall my book was the campus read at Stevens Institute of Technology; I joined them for the September convocation. I was also the ‘24-’25 Bickford Visiting Artist at the Cleveland Institute of Art and the Myers Distinguished Visiting Fellow in the Humanities and Civic Engagement at the University of Scranton. An engineering school, an art school, and a Jesuit liberal arts college! It was so gratifying to connect with all three communities over ideas about disability and design.

I’ve got work in upcoming exhibitions at the Victoria & Albert Museum and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Seoul.

My first short film Simple Machine will be in six festivals and counting this year. We got the Audience Award for short docs at the Independent Film Festival Boston and a best documentary award at the West Chester Film Festival. More to come — reach out if you might like to plan a screening and companion event together. It’s 23 minutes, so it’s easy to attach to a series or talk.

Never would I have ever expected such soulful medicine in an essay about prototyping - such deep delight and inspiration here. Thank you.

Thank you for this! I am trying to take on a new perspective: to focus on creativity and all the positivity that comes directly from it.