"is this what I signed up for?"

engineering, ethics, and the classroom: an audio series called Sketch Model

[This is undefended / undefeated, a newsletter from Sara Hendren that you signed up for at some point. Upcoming newsletters on design education, bioethics, the liberal arts and how they liberate, and more. Unsubscribe at any time by scrolling down to the bottom.]

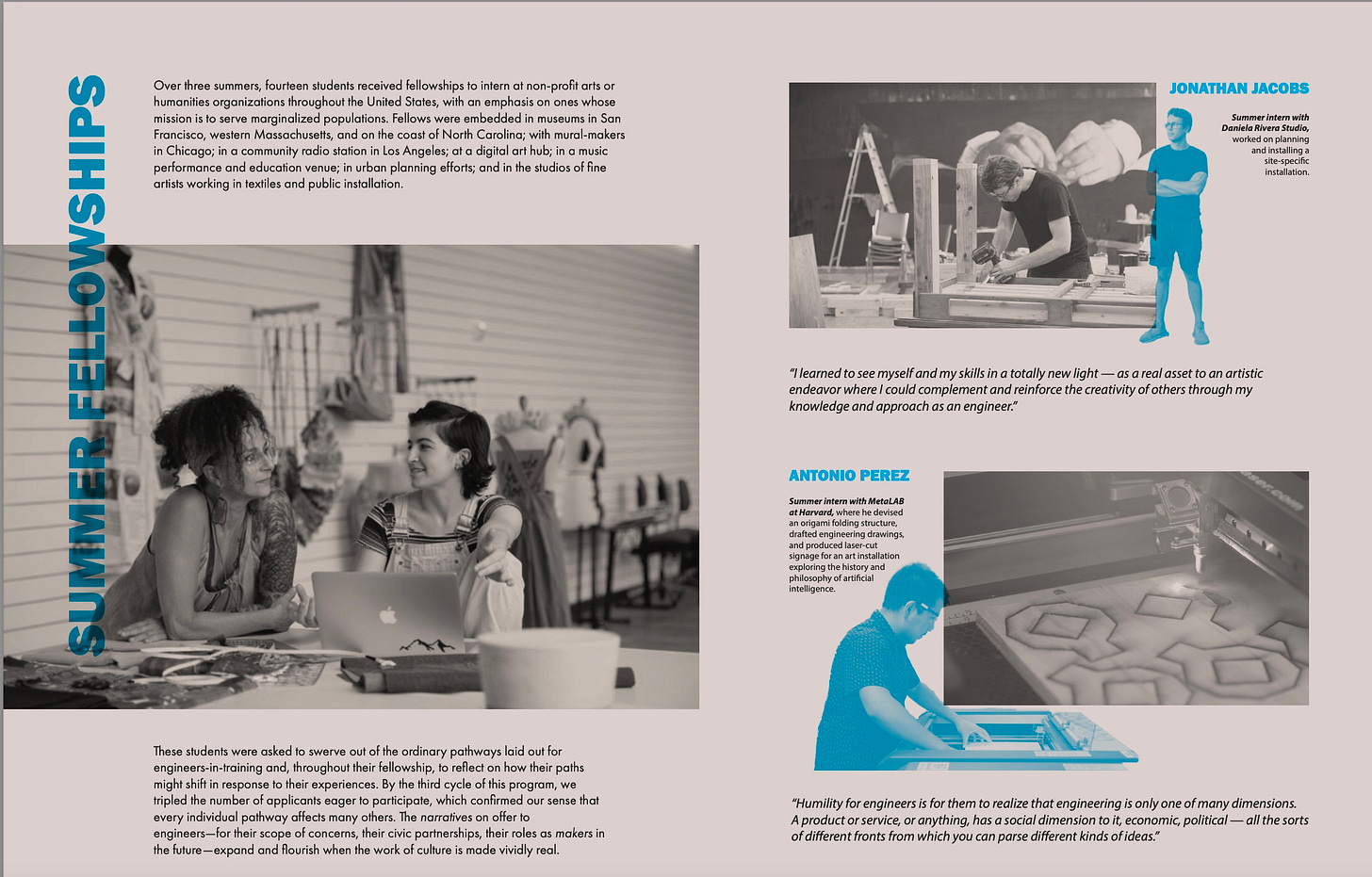

If you work somewhere in tech, like me, you may be 1) preoccupied with worries about the technocratic thinking that’s everywhere in our daily lives, and 2) weary of the vague hand-wringing response that’s the dominant rhetorical mode for Big Tech Backlash. For the past several years, I worked with a team of faculty and staff at Olin on a project called Sketch Model. In its first phase, it was a series of programs—residencies, fellowships for students, and investments in STEM-humanities faculty partnerships—that brought a distinct energy for humanities-led ethics to our campus. You can read all about the things we did, and why:

And you can also listen to a bigger-picture look at the issues at the heart of Sketch Model on our podcast:

How is the engineering classroom a key site for understanding the recurring atrophy of ethics in tech? What’s behind the documented de-politicization of young engineers over a typical four year undergraduate degree? And what kinds of practices might support an engineering classroom with a robust and dynamic ethical connection to a complicated world? You can find it on Spotify, Apple podcasts, and other platforms around the web.

Here’s an excerpt from episode 2, from conversations I had with Virginia Tech’s Matthew Wisnioski and RPI’s James Malazita. Lightly edited for written clarity:

Sara Hendren: Take us there, to the turn in the 1960s. What issues are on engineers’ minds in a new way? What's providing a seed of doubt about the promise of technology compared to, for example, the big optimism of the post-war era?

Matthew Wisnioski: So by the end of the 1960s, there are a wide range of broad societal critiques that are coming from lots of different places. Some of them include the rise of the environmental movement. Others include the civil rights movement, living in the shadow at the atomic bomb and the Cold War. And at the center of all of these issues is this new concept called technology. Technology starts to be identified as the driving force between a lot of these societal problems. And then you have engineers who in World War II and beyond tie their very sense of self to this notion: that they are the bringers of progress through technology. So they're looking at this world in the 1960s and saying to themselves: On the one hand, we're putting people on the moon and this is the height of progress. And: now all of a sudden we're being accused of bringing civilization to the brink of collapse. That sounds a little apocalyptic, but there was a lot of writing at the time and thought at the time that put the stakes that high.

And so you might imagine that that prompted a lot of defensiveness on the part of engineers who looked out and said: You say that we're the root of all evil, but we’re the people who brought you your refrigerators and your air conditioners and your cars and your stereo and this kind of material wealth that keeps society going. And yet at the same time, engineers are really close to the inner workings of the military industrial complex, which is a concept that emerges at that time.

So they see what's going on behind the scenes, and they look at these claims of progress that are being made and that are often being made by the same companies that they work for… And they also start to question, okay, maybe it was a good idea to get trained up to work on military and technology during the WWII. But we seem to have never demilitarized. And we seem to be constantly seeking a military conflict and a buildup of weapons systems and the amount of investment between the state and a few large companies just keeps growing. And: is this what I signed up for?

In this same episode, I talk to James Malazita about the kinds of work he does in his Tactical Humanities Lab at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, mixing laboratory-style coursework with critical perspectives from the humanities. We talked about C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” essay, and how hard it is to figure out a way around that enduring story.

James Malazita: Rather than just teaching students what they know—so, filling their minds with various facts, various technical expertise—education [also] operates epistemically, in that it shapes how students know and how they imagine different types of knowledges relate to their core expertise. First, whether or not things like social concerns, political concerns, environmental concerns are a part of what it means to be an engineer, or what it means to be a computer scientist in the first place. But then, second, how they imagine their own expertise and their own capacity to speak to and challenge some of these larger social concerns or political concerns of technology. So it's this really interesting, and, frankly, quite effective double bind, where it gives permission for folks who aren't particularly interested in social concerns to displace any criticisms of themselves while also trapping STEM educators and STEM students who are interested in technical concerns into the feeling that they don't have the ability to speak, much less act, upon those concerns.

Sara Hendren: Listeners to this series may be thinking of a well known set of ideas that describes this phenomenon pretty well, and from way back. That's writer and thinker C.P. Snow's lecture from 1959 called “The Two Cultures.” And it decries the big gulf between the intellectual culture of the humanities and that of the sciences. James reminded me that the legacy of this two cultures idea is a long one:

Malazita: C.P. Snow's famous “Two Cultures” paper describes the sciences and the humanities as having fundamentally incommensurable or incompatible worldviews— particularly that the sciences, engineering, and mathematics value truth claims that are empirically grounded and falsifiable, whereas the humanities and history and literature value truth claims that are more interpretive, more subjective, more qualitative. And the interesting thing about this essay is it's difficult to parse apart how much C.P. Snow was analyzing or describing a situation that he observed in the academy, versus how much this essay is actually weaponized to reproduce that situation. As in: STEM scholars and humanities scholars will actually invoke Snow's “Two Cultures” in order to short-circuit any collaboration between the two.

Hendren: And I've heard you say the remedy is not, therefore, to have more humanists in the room, that somehow just the “getting together of folks in the classroom” would magically resolve this. Sometimes I have found myself saying to young engineers—in my case, my students are all engineering majors—sometimes I say, well, my vision of the good for them is actually to know where there's a hard stop on the kinds of expertise that they can marshal in a technological issue. To know at least which domain the expertise they need lies in, and how to call up that person. Like calling up that person when they're in a bind. Even if it's outside of a professional context. If you're in a urban planning discussion, say, with your local community and somebody thinks it's a matter of how many automated crosswalk signals you're going to have or whatever, then you realize: Oh, no, this is actually a question for a human-centered anthropologist to figure out how we use the street.

I keep thinking: It's not that I expect a young engineer to be able to perform all the duties of an anthropologist in that moment. It's actually precisely the humility that I want for them. To say: I know what I don't know, which is that this is an anthropological matter, and I'm going to cede my technological expertise—expertise that people tend to be so deferential to in these moments—cede it to the anthropologist that we gather in the room. That scenario may be one horizon for an engineering education. But how does that scenario, how does that land for you?

Malazita: Yeah, so it's interesting. On the one hand, I totally agree with this. We cannot train engineers and scientists to believe that they have the God's eye perspective on everything. And in fact, David Noble wrote about some of these very early integrations of philosophy into engineering curriculum, in the twenties and thirties, and said, one of the reasons that they failed is because engineers would read Plato's Republic and then say: Well, now I'm done. Now I know what the ideal society looks like, and I will just implement that. So that is not the type of education that I would advocate for in terms of a hybridized STEM education.

And I like the idea or the use of the word humility, acknowledging where expertise begins and ends, who belongs in the room and whose voices need to be represented in various decision-making processes. The concern I have with the humility model—or, all we need is more anthropologists in the room—is how easy it is to offset that type of collaborative decision-making into essentially a checkbox ethics system.

The whole series is one our project web site—with a full-color brochure about our programming—and on Spotify and Apple podcasts and elsewhere. I’d love it if you shared it with folks who might be interested.

Listening: Waiting for my vinyl copy of Dan Phelps’s Modular: Sonic Explorations, via my friend Claire.

Watching: Éric Gravel’s Full Time. We went as a family to a screening at the MFA’s French film festival in late summer. Reader: the MFA is on the sludgy and inconvenient green line. Parking is terrible. The theater is in the bowels of the museum. And it was sold out! Hundreds of people there. The film curator was practically levitating—a full house for this cinematic short story told as a thriller, but utterly small and character-led. Hollywood, I beg you: the people are hungry as ever for story.

Words: I wrote about Rebecca Horn’s Finger Gloves for Art in America’s October print issue, part of a series called “Impairment as Impetus: Five Historic Works Spurred by Disability.” (open access)

Voice: I spoke at the inaugural symposium for MIT’s new Morningside Academy of Design this month, on a panel about design education. My remarks are—surprise!—a defense of the humanities. The panel is Event 3, here.