"if you can't get out of it, get into it"

hyperlocal streets, the social glue of strangers, critique + repair, "Areas of Moral Clarity."

December 19, 2020

If those ten words sound a little woo, a little "tune in, drop out" a la Timothy Leary to you, you're not alone, I’m sure. But that's what Parker Palmer talks about in his book Let Your Life Speak, and the simplicity/profundity thing landed for me this year.

[Hi—this is Sara Hendren's newsletter that arrives on occasion. You signed up for this newsletter directly at some point, but if you change your mind, do please unsubscribe any time.]

Parker Palmer tells the story of a weeklong class with Outward Bound, an outdoor education group, during which he was given a rope and instructions to rappel down the face of a cliff. It was his first time. He got to flailing, fast—frozen in place by the sight of the drop beneath and unable to listen to the commands being called to him from the safe ground above. When things came to a stalemate, his instructor said those ten words, the motto of Outward Bound: "If you can't get out of it, get into it."

I happened to be listening to Palmer's book this summer, chosen by instinct alongside other inner-life thinkers like Pema Chodron and Richard Rohr while getting "into it," in my own way, by strict necessity. I didn't travel anywhere this year; the only journey each day was in hyperlocal walks—only in the nearby dense grid of one-way streets in my immediate neighborhood, and only at a very (very) slow pace. This was in May, June, July evenings. My regular city run happens in the mornings in all weather. But in a pandemic, I needed to mark the end of the day, too. After dinner, headphones on, I made my difficult peace with the impossibility of getting out of things. Sometimes I only wanted more space, of course. Some escape, some literal or figurative distance from the limitations and the big uncertainty that marked the whole year. But in Palmer the message was: Sure, take the space when you need it. But another choice might be possible. You might get way, way closer.

I don't think this is a "stop and smell etc" kind of invitation, you know? Outward Bound understands that we're all going to be trying to get out of situations, and rightly so. But when constrained in extreme, perhaps there's a way of not just acceptance but of tunneling deep, going absolutely micro in the face of macro-nothingness.

So this was the year that I witnessed things like: the impossibly small vegetable gardens in the tiny community plots in my neighborhood. And other people's "yards," which are almost entirely small patches around a front porch or clinging to a fence here and there. A line of tomatoes along a wall. (The most hopeful of the gardens in my neighborhood consisted of a handful of ratty old buckets growing a single chard, say, or a sprig of rosemary, and placed on the front steps of a house on a busy street—so trusting.)

Instead of straining at the edges for a getaway, what happens when you go in the extreme opposite direction? I tried to go deep into what's close by. Maybe you did too—kicking and screaming on the inside, but resigned to the confines. And then moving closer, maybe as close as one can get.

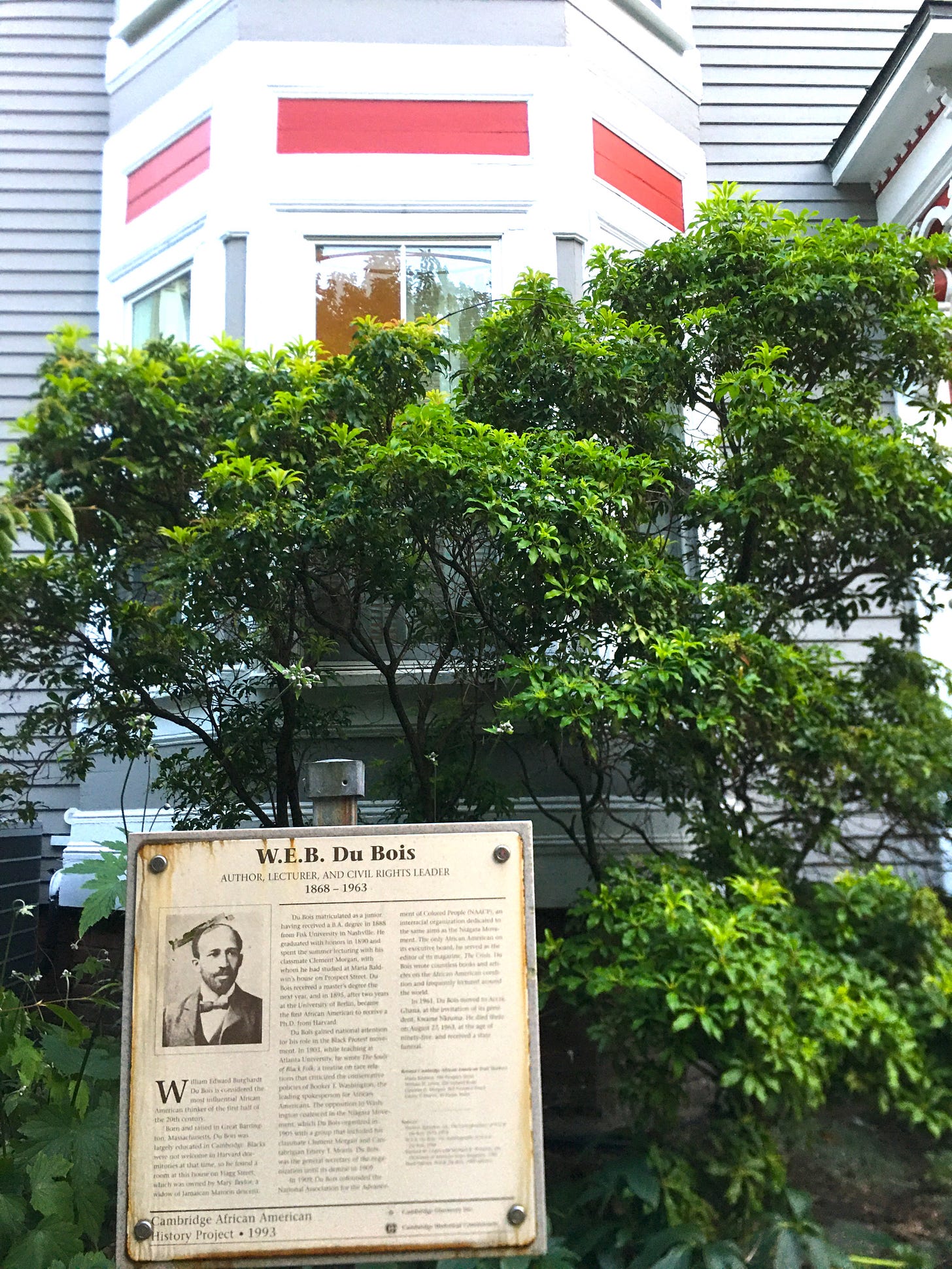

Anyway, I saw a lot this summer. Cambridge has history you can trip over—commonplace markers of the famous wars, and one-time residences of our best Americans:

All the stuff I'd been missing, right? There was lots to see. But even with dozens of walks, the repeat evenings watching the incremental growth of basil and roses—I was unprepared, one night, to re-discover the feature of the neighborhood I'd been missing the most this year: sharing city life with what Louis Wirth called "secondary contacts." Those are the people in and around the neighborhood. They're not the primary contacts of our family. They're the people we see on our commute or at the shared favorite cafes. They're the glue of reassurance, usually, that our locale is our own. It was on one of these walks that I realized I had forgotten Greg, one of my secondaries. Greg was a dad at the park, someone I would see for unplanned play dates when our kids were young. We exchanged a couple of emails, but we never got to know each other. We lost touch entirely. And then I found him, on a walk in the neighborhood:

So I got into it, I guess Palmer would say. And now the books I buy, when read, all go to Greg's library. And from there they scatter out to other secondary contacts, little tributaries all over the neighborhood.

The last few months I wrote some short pieces: my wish for a laptop version of Errol Morris's "Interrotron" for Zoom life and my call for technologies as modes of both critique and repair, with an eye toward the hiring of a new MIT Media Lab director. I also adapted a piece from my book about the history of curb cuts as precursors to our changing streets under COVID-19. And I did some dwelling on Dr. Paul Farmer's idea about living with "A.M.C.s"—Areas of Moral Clarity—in a meditation on bioethics, democratic pluralism, and the value of human life. Plus more ideas from Francis Spufford, Edward Said, Elizabeth McCracken, and others here.

My book came out in August, and it might be for you. It got a generous review in the New Yorker and elsewhere this year, and it was included on the Best Books of 2020 lists at NPR and LitHub. It's a book, above all, about the universal experience of assistance in all our lives: designed or demanded, technological or human. It's a plea for a future with assistance resolutely in it. And if you're more keenly aware of your own body and its changes, its frailties, its needs this year, well—I hope you'll read it.

I've joined up with New_ Public, led by Eli Pariser and Talia Stroud, as a Contributing Editor, and my plan is to write more there, and here, and in other venues, and to be much less on Twitter, if at all. I'd love to stay connected! Reach out with what's on your mind.

Here's to more light on the horizon.

I’m Sara Hendren. I’m an artist, design researcher, writer, and professor at Olin College. My first book What Can A Body Do? How We Meet the Built World was published in August 2020 by Riverhead.