"everything you learn you're only rememberin'"

recall, reflection, + making sense

April 10, 2020

That line is from "First in Flight" on the Blazing Arrow record by Blackalicious.* It caps a run of verse offering that zen vibe of you-already-know. As in: you already know what needs knowing—it's right there, available for the taking. Maybe, like me, you're wondering right now: Do I? What do I know for sure? Breaking news is keeping me smart and informed, but it's not clear where the real learning (to say nothing of wisdom) will come from. Is it a matter of recall?

Here's how that passage from "First in Flight" starts: RISE!—

(Hi—this is the first newsletter in Sara Hendren's Undefended/Undefeated. You signed up for it, but that may have been a while ago. If you're not longer interested, do please unsubscribe, friend.)

RISE! If you're sleepin' won't you open your eyes again

The greatest high be that natural high within

No need to force the progression just ride the wind

You'll know the answer to the where and the why and when

If you keep workin' for your search you will find the end

Though at the end you find it only begins again

See at the end you'll see it only begins again

And everything you learn you're only rememberin'

It's a long-running theme in some of the world's contemplative traditions: that our real insight might come from waking to what's already inside us. That the light of understanding was always present, that removing the effort from trying to "get somewhere" might be the way to arrive. It's in wisdom traditions and in pop culture alike, this exhortation to remember. Remembering—as in, tapping self-knowledge?

It'll test your first principles, for sure. I find myself too swayed by the evidence of widespread human fallibility—including the human tendency toward self-deception—to accept the idea that all learning is somehow self-recall. But remembering, understood with a wider definition, is something I think about a lot.

My institution, Olin College of Engineering (now with a brand-new president, Gilda Barabino!), operates in the tradition of experiential education, a big canopy of thought built on the basic idea that students are best trained when the practice of learning is foregrounded. Some classrooms, like ours, make it real via hands-on learning, or its variant, project-based learning. Experience-driven work can flourish at an engineering school, as you might imagine. My encounters with students sometimes have parts and circuits on the table between us, and sometimes they look like this:

That's me on the right, in one of the studios where I teach a class (alongside five other faculty) on participatory design. The four students here have conducted a bunch of interviews off campus, shadowing people unlike themselves in their daily lives (in this case, animal care workers). They're doing a beginner's version of ethnographic research and then coming back to the studio to make sense of what they've learned. All those notes and drawings are the visual ways they're trying to account for the complexity that comes with studying the human animal in its many weird contradictions.

The work like this goes toward a design proposal at the end of the class—an evidence-backed idea, built on a semester-long hard look at the assumptions they started out with. What would a desirable future for this group of people look like? Is it a product, or a service, or something else? They present it to professors in dozens of meetings like this and in regular formal reviews. When students have given me a big report-out, I prepare a bunch of observational comments and recommendations. But first I ask them a question that's about recall: How do you think you did just now?

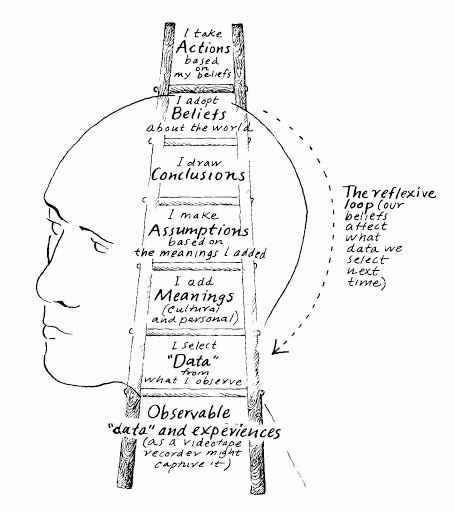

What many folks miss about experiential education is that the research says it's not exactly the "interactive" doing itself that's the key; it's the doing and reflecting upon that doing, afterward.** Here's one of many ways of expressing it:

It's in the remembering—which means editing, of course, and parsing and making sense of what happened—where the learning solidifies. At Olin, we teach for that, too, asking for regular written reflections as a part of normative practice.

But my question—how do you think you did just now?—is asking them to remember not just the content of their work, but to recollect something bigger: that if they want to grow, they need the capacity for honest self-assessment. I want them to remember that the exchanges at the table, teacher to student and back, are worthless if we don't treat them as the honest chance to get better at something. I give them a minute to resist the urge to defend whatever it is they did, and instead to look back and size it up clear-eyed, unvarnished. I want to see if they can just name it when something was completed at the last minute, or when the renderings don't live up to their good insights, or where the strengths and weaknesses show. And I want to model a collective practice between us: remembering as making sense, and remembering as becoming.

So—lots of us live in want of memory right now, I'd wager. We are recollecting and revisiting the books and songs and movies that got us through other times of big sadness or uncertainty. I find myself sticking by the enduring ideas that were available prior to a global pandemic, that take on new meaning as it plays out, that will be an invitation, beckoning still more in whatever comes after. You and I are probably saying the words associated with our own wisdom traditions or the words people said to us or sang to us before, out of habit or out of necessity.

Some of you know I've written a book about design and disability, about the ways all of our many bodies greet the world with adaptive, stunning creativity and vital urgency, in the everyday tools we use and the environments where we live. I got to remembering with a bit of that design mix last weekend, during one of a zillion video conferences with friends and colleagues. I'm providing captions for a Saturday night gathering here, typing along as people talk or play songs. And it turned out that my old friend Jason Harrod, who's singing to the group in this image, chose a song I know in my bones. I had to stop my itchy thumbs from typing ahead, I know those words so well. They got me through many bad days in decades past, and here they are again, now made into caption-verse in a screengrab from another attendee:

For me, those words get it right in the present day, but they're fortified most of all by memory.

* That whole Blackalicious record is a stunner. The extended coda on “Aural Pleasure” is a guaranteed runner’s high for me.

* Thanks to my colleague Jonathan Stolk for the reference to the Reflexive Loop.

I’m Sara Hendren. I’m an artist, design researcher, writer, and professor at Olin College. My first book What Can A Body Do? How We Meet the Built World was published in August 2020 by Riverhead.